This ancient art form evolved on the northwest coast of North America at least some several thousand years ago. The West Coast People have lived in this area for over 20,000 years. The art form is primarily associated with artists from Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, Heiltsuk, Nuxalk, Kwakwaka’wakw (Kwakiutl), Nuu-chah-nulth, Salishan and other First Nations tribes. With an abundance of animal, salmon and cedar trees there were enough resources for the people to live and develop a large civilization based primarily on tribes and a clans. The people lived closely with nature and most of the clans adopted animal or birds as their mascot. The majority of their art was abstract and used for decorative purposes while having symbolic meaning. Utensils, woven cloths and blankets (Chilkat blanket), storage boxes (bent boxes) walls of cedar dwellings and house poles (totem poles) were decorated with their art work. resurgence in the popularity of the art form. There are now many aboriginal and non-aboriginal artist producing original and contemporary pieces in wood and metal, prints and graphics.

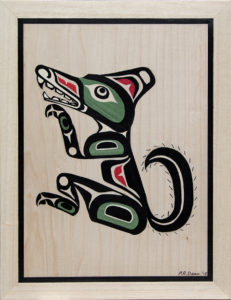

The design rules include the use of form lines and design elements that include ovoids/circles, crescents, U forms, S forms and trigons as fillers. Originally the form lines were painted black and the shapes were painted red. Sometimes the negative spaces were left unpainted or painted white. Later blue and green colors were used to paint the secondary elements enclosed in primary elements. See Figure 2 – the Haihais Sitting Wolf. The black form lines define the different segments of the animal, while the various elements like the ovoids, crescents and U forms define the interior part.

Form lines are curvilinear and vary in thickness, much like calligraphy. Form lines are usually outlined and then filled in. Primary form lines are negative as they are the space between patterns. Symmetry was used particularly when representing birds, see Figures 3 and 4. In early forms of the art, perspective was not used. Some contemporary artists are now using elements of perspective, see Figure 5. The light source is not defined nor are any shadows shown.

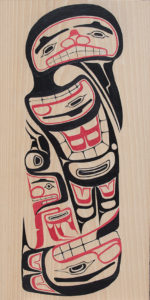

Often the object being decorated defines the space. Figure 6 is a representation of a print by the artist, Robert Davidson, in Marquetry. The artist used the Haida legend of the Raven stealing the Moon as the subject. The print was based on a wood carved panel in which the artist composed the design to fit completely within the confines of the panel. The anatomies of the Raven and the Fisherman were rearranged in abstract form. This example is the very essence of complex Hiaida designs.

Figure 7 is another print by the artist Robert Davidson, Raven with a Broken Beak and the Blind Halibut Fisherman. The head of the Raven is at the bottom of the picture. The beak is broken after being entangled with the fisherman’s hook. From the neck a gracefully sweeping wing delineates the bird’s body. The fisherman’s head is at the top of the picture. Behind his head are the tail feathers of the Raven and below is the Raven’s claws. There are human feature in the Raven’s anatomy signifying the transform powers of the bird into human form. Again this is another example of filling the space being more important than the correct positioning of the body parts.

Piet Mondrian (1872 – 1944)

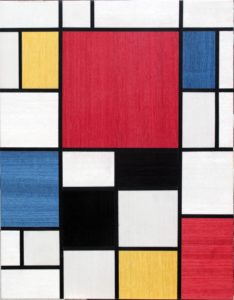

While I was researching the Native Art of the Northwest Coast, I had the opportunity to visit the Tate Gallery in Liverpool, England. It was at the Tate that I saw the exhibition of Piet Mondrian studio and some of his work. I was immediately struck but the similarity of his art form with that of the Northwest Coast Art. The use of black form lines and the limited palette; red, blue, yellow and grays. According to The Art Story web site (http://www.theartstory.org/artist-mondrian-piet.htm)

“He radically simplified the elements of his paintings to reflect what he saw as the spiritual order underlying the visible world, creating a clear, universal aesthetic language within his canvases. In his best known paintings from the 1920s, Mondrian reduced his shapes to lines and rectangles and his palette to fundamental basics pushing past references to the outside world toward pure abstraction. His use of asymmetrical balance and a simplified pictorial vocabulary were crucial in the development of modern art, and his iconic abstract works remain influential in design and familiar in popular culture to this day.”

It was interesting to note however the different use of the form line. In the native art the form line was curvilinear while Mondrian excluded curved lines from his painting.

“More and more I excluded from my paintings all curved lines, until finally my compositions consisted only of vertical and horizontal lines, which formed crosses, each one separate and detached form the other. Observing sea, sky, and stars, I sought to indicate their plastic function through a multiplicity of crossing verticals and horizontals” – Piet Mondrian, 1941

Figure 8 is a representation of one of Mondrian’s paintings from the 1920’s. Notice the palette consisting of black and white and the three primary colors, red, blue and yellow. In Figure 9, I tried to replicate the form of the painting using natural wood veneers of a similar tone.

Figure 10 is a representation of Mondrian’s painting, No. VI / Composition No. II. In this painting he introduced a number of gray tones while reducing the thickness of his form lines. In representing his painting in Marquetry I believe I was able to capture the “balance of unequal but equivalent oppositions” that Mondrian tried to achieve in his attempt to capture a “dynamic equilibrium”. – Tate Gallery September 22, 2014.

References

Northwest Coastal People – http://firstpeoplesofcanada.com/fp_groups/fp_nwc1.html

Gilbert J. and Clark K. (2001) Learning By Doing, Pacific Northwest Coast Native Indian Art, Raven Publishing Inc, BC, Canada

Gilbert J. and Clark K. (2005) Learning By Designing, Pacific Northwest Coast Native Indian Art, Volume 1, Raven Publishing Inc, BC, Canada

Gilbert J. and Clark K. (2007) Learning By Designing, Pacific Northwest Coast Native Indian Art, Volume 2, Raven Publishing Inc, BC, Canada

Holm B. (2015) Northwest Coast Indian Art, An Analysis of Form, University of Washington Press, USA